White People Listening Gangsta Rap Funny

The controversial music that is the sound of global youth

(Image credit:

Nasecworld / Believe

)

In the last decade, drill music has become ever more popular while inspiring debates over its links to violence. Now the rap sound is flourishing in many continents, writes Sam Davies.

I

In 1965 Martin Luther King arrived in Chicago, looking to expand his civil rights campaign beyond the American South. He found a deeply divided city, not governed by the Jim Crow laws which separated southern states, but equally segregated by socio-economic disparity and divisive housing plans. Much of Chicago's black population lived in slums on the south and west sides. King left in 1966 after agreeing an improved housing plan with the mayor. But by March 1967 he himself admitted that much of his work had already been undone.

More like this:

– The greatest hip-hop songs of all time

– How rappers are resurrecting punk spirits

– The exhilarating songs of street protests

Less than 50 years later, Chicago's deeply disenfranchised black communities gave birth to drill, a rap sound that has since spread to London, New York, Paris, Amsterdam, Lisbon, Stockholm, Sydney, Dublin, Seoul and Kumasi. Named after a slang term for attacks between gangs, drill is ominous hip-hop with lyrics – like trap and gangster rap before it – about drug dealing and street crime. What distinguishes drill from other forms of hip-hop is its combative energy and its particular concern with gang conflict and murder. Whereas trap, the Atlanta-born rap style that dominated hip-hop for most of the 2000s, is often rhythmically rigid – with a snare falling on the third beat of each bar – drill moves to skippy, syncopated hi-hat patterns echoing the rapid fire of a machine gun.

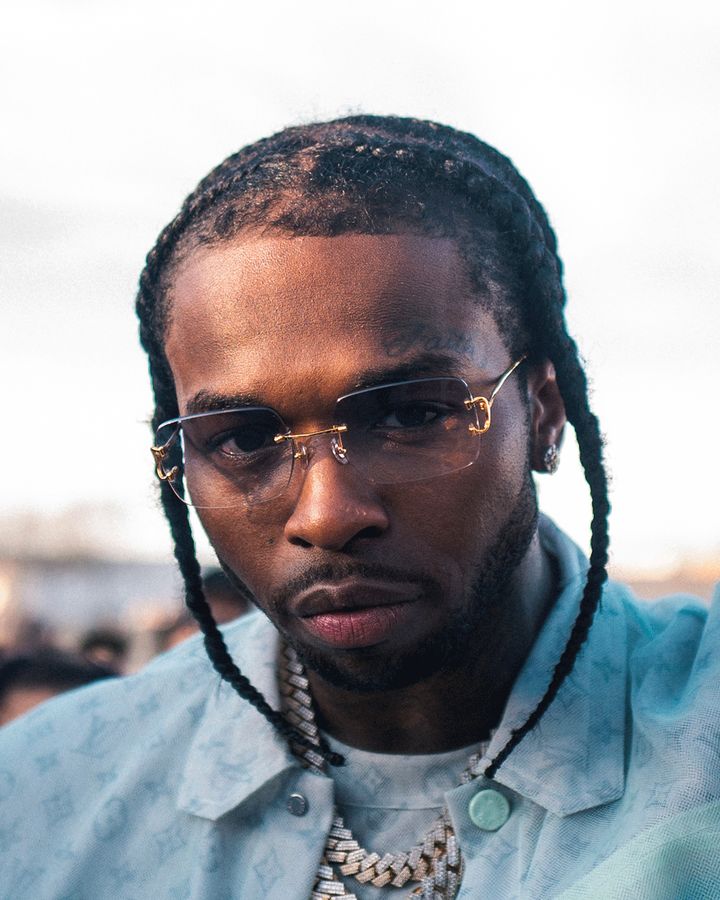

The success of the late US drill rapper Pop Smoke was a watershed moment for the genre – changing what it meant to make drill (Credit: Jauris Bardoux)

As controversial as it is popular, from the beginning drill has been accused of encouraging violence among its youthful audience. But drill's impact is indisputable, placing it among the most important cultural phenomena in a generation. In a late-2019 Pitchfork feature anointing drill "the Decade's Most Important Rap Subgenre", writer Alphonso Pierre noted that, despite the controversy, drill had spread to a global audience thanks to its frank, lurid portrayal of urban life: "The stories were often sad, teenage rappers forced to grow up early thrust into the spotlight. Some were against the genre's candid depiction of violence, but this was the real world these rappers lived, and thus rapped about, a world borne of conditions that racism helped to create." Pierre also referenced drill's impact on Cardi B, one of a number of rap superstars also including Drake and Travis Scott, to cite its influence.

The birth of drill

Pinpointing drill's genesis is difficult, but many credit Pac Man, a rapper from Chicago's South Side, as the first to use the term in a musical context. In 2010 Pac Man released his one and only mixtape I'm Still Here, featuring a song called It's a Drill, its title a play on the word's many possible meanings. As a slang term, "drilling" meant attacking a rival gang with gunfire. "We still out here drilling man," Pac Man intones on another track from I'm Still Here. "Drilling" is one term among many in drill's original slang dialect, along with the omnipresent "opps" (opposition, competitors), "bando" (abandoned house, used to sell drugs) and "L" (referring to the defeat or loss of a rival).

Drill's immediate popularity owed to two of hip-hop's most prized values: authenticity — or realness — and storytelling. The stories told by drill artists were unbelievable. Lots of them were true. In 2012 drill had its first mainstream hit in 16-year-old Chief Keef's boisterous single I Don't Like, which reached number 73 on the US Billboard Hot 100. But drill's rising profile was soon hampered by the very violence it had been named after. Pac Man was killed in 2010. Lil Jojo, an 18-year-old drill rapper and known adversary of Chief Keef, was killed in 2012.

Inevitably these events overshadowed the music. Commentators called on record labels to drop rappers who encouraged violence, echoing the censure of gangsta rap in the 1980s and 90s. The entire hip-hop genre was born from urban disenfranchisement, kids in the most derelict sections of the Bronx, in New York, congregating at block parties in the street because they were too young or poor to get into discos. Once hip-hop's popularity had spread to the west coast, artists like the California crew NWA began making what came to be known as gangsta rap, which viscerally depicted the gang crime on the streets where they lived without judgement. As the music's popularity grew throughout the 1980s and 90s, so did police interference, building tensions epitomised on the NWA single Fuck Tha Police. In response, the FBI wrote to NWA's record label complaining that the song encouraged "violence against and disrespect for the law-enforcement officer".

But while NWA described notional anti-establishment violence in their tracks, drillers rap about specific violent incidents in which they themselves are the perpetrators. The veracity of such lyrics is the subject of debate in internet forums and, recently, court rooms. From the genre's birth, the belief that drill music has to be linked to real-life killing has maintained a sinister presence in the scene. As the genre becomes more mainstream most listeners and artists have broadened their definitions, but even today it doesn't take much searching on message boards or social media to find fans arguing that music isn't really drill if the rapper isn't really drilling.

Offica is a drill rapper from Drogheda, a tiny Irish town 30 miles north of Dublin, who believes "violence in drill is kind of departing" (Credit: Offica)

Street Newz TV, a YouTuber who posts videos about the chaotic inner conflicts of the Chicago drill scene to nearly 200,000 subscribers, defines drill in largely non-musical terms. "The drill scene is based on you putting in work in the streets, getting on wax and talking about it," he says. By "work", he means drilling, ie murdering. He identifies 745, a 2006 track in which Atlanta rapper Gucci Mane purportedly referenced an incident where he shot and killed someone, as the first ever drill song (most fans believed the victim apparently referred to was an associate of Young Jeezy, a rapper embroiled in a war with Gucci Mane).

In spite – or perhaps because – of the controversy, drillers like Chief Keef attracted widespread attention. But the drill sound now permeating the globe is markedly different from that of the early Chicago artists. Before reaching a truly international audience, drill spawned a vibrant London scene, where the music underwent a number of crucial developments. Among them were production techniques that became key to the updated formula, most notably the addition of deep surges of bass – variously described as revs, growls and slides – at the end of each bar, playing out quick mini-melodies rarely heard at such low register in other genres.

Corey Johnson, a former rapper and veteran of the British rap scene who witnessed much of UK drill's earliest iterations at his Defenders Entertainment studios in south London, says producers and engineers added these sounds to compensate for rappers not providing enough lyrics to fill bars. "They're just going on the tune, saying what they got to say, and then they're done," says Johnson. "'But brudda, you gotta say a few more lines!' They're like 'nah', so the engineer's having to do the ah-ah-ah-ah. That's coming from real kids off the street that don't know how to count music, then become this thing that everyone's into."

UK drill is also linked with gang conflict, though in London "drilling" gained a new meaning. In a 2017 report in Fact magazine, a teenager from a Brixton youth centre is quoted as saying: "If Chicago drill is a gun, ours is a knife". While UK drill rappers still referenced firearms, they added slang terms like "rambo" (knife) and "splash" (stab) to the drill lexicon. "Opps" remained. While the nature of the violence referenced was different from Chicago, the controversy it generated was much the same. In 2017, rising numbers of London stabbings prompted mayor Sadiq Khan to criticise YouTube for failing to remove drill videos which, he argued, glorified knife crime. In May 2018 YouTube responded, removing more than 30 videos after being petitioned by London's Metropolitan Police. A month later west-London drill crew 1011 were banned from making music without police permission. Then in 2019 drill duo AM and Skengdo received suspended prison sentences for performing a song at a London show. Meanwhile tabloid newspapers criticised Apple and Spotify for "selling banned violent drill music".

Moving beyond violence

However, while the relationship between drill and violence has remained a matter of live debate – and, many would argue, central to its very existence – drill artists around the world have increasingly added new facets to the genre. As the influence of UK drill spread back across the Atlantic, among the most significant of a new wave of US drill artists was Pop Smoke, a drill rapper from Brooklyn who achieved viral fame in 2019 after working with London producer 808Melo. But while Pop Smoke rapped about opps, violence was never the emphasis. His lyrics were designed to make fans laugh, swoon, dance or even jerk tears: "Welcome to the party," he growled in one of many viral hits.

A new collaboration between Ghanaian drill artists Smallgod, O'Kenneth and Kwaku DMC and UK acts Headie One and LP2Loose shows drill's global spread. (Credit: Nasecworld/Believe)

For many, Pop Smoke signified a watershed moment for the genre, changing what it meant to make drill. "You can use drill beats and not talk about drillings," says Offica, a drill rapper from Drogheda, a tiny Irish town 30 miles north of Dublin. "Pop Smoke was a perfect example of that." In late 2020 Offica and his crew A92 recorded Plugged In, a freestyle that became a hit after thousands used snippets of the track to soundtrack their TikTok videos. "That's the good thing about TikTok now," Offica says. "I think the violence in drill is kind of departing, because everyone's… having fun, dancing, d'you get me?"

In the last two years especially, drill has started to look like a truly global movement. French drill emerged "with the sound of the English scene in one ear and Brooklyn in the other," as French music magazine Les Inrockuptibles reported in May 2020, while much of Europe followed suit, with artists in Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and Poland making drill largely indebted to Pop Smoke and the UK. In 2019 Pop Smoke's influence hit Africa, with drill scenes emerging in Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Mozambique. ChicoGod, a drill rapper from Kumasi, Ghana, was at a rave when he heard drill for the first time. "I was like 'what is this?'" he says. "It was so different. The way it played out from the speakers was so magical, so I had to Shazam the song and I realised it was somebody called Pop Smoke. I think by the end of the week everybody I knew was caught up on Pop Smoke." The subsequent Kumasi scene bore such a resemblance to what was going on in Brooklyn that many started calling it "Kumerica". By 2020, popular drill artists could be found in countries as far-flung as Sweden, Brazil, Australia and Korea.

But adversity was never far away. In February 2020 Pop Smoke was shot and killed in Los Angeles at the age of 20, by a group of teenagers intent on stealing his watch. Three days earlier he was due to play a show in Brooklyn, but was forced to cancel under pressure from police. Like drillers in the UK, Australia and Europe, Pop Smoke's alleged gang ties made it difficult for him to perform in his hometown throughout his career.

The debate over its policing

Despite the pandemic halting all live music last year, drill's rise has continued. In October 2020, London drill artist Headie One scored a British number one with his debut album EDNA. Only last month, Russ Millions and Tion Wayne topped the UK singles chart with their song Body. But attempts to censor the sound have continued too. In November 2020 the BBC aired the documentary Defending Digga D, examining the strict legal procedure by which one of the UK's biggest drill artists is allowed to release music. Having previously served a prison sentence for conspiracy to commit violent disorder, Digga D must now run all his lyrics past a lawyer to ensure they are not deemed to be encouraging violence, with mentions of opps and even certain places (like Ladbroke Grove, where Digga D grew up) edited out of tracks.

On his recent mixtape Made in the Pyrex, which reached number three on the UK albums chart, Digga D raps: "Numerous shootings, the mandem do this, trust me, it's more than music". The lyric chimes with an idea that drill isn't even about music, that songs are above all a means of celebrating dominance over rival gangs. From this angle drill sounds like a canary in a coal mine, the sound of a society tearing itself apart from the inside out.

The popular UK drill musician Digga D must now run all his lyrics past a lawyer to ensure they are not deemed to be encouraging violence (Credit: Elliot Hensford)

While continually ordering the removal of drill from YouTube, police also use lyrics and videos as a resource for prosecution. Earlier this year the BBC reported on 70 trials across the UK where drill music was used as evidence in court. Despite criticism, police have defended this approach by pointing to specific incidents where the release of drill songs online has led directly to violence. For example, in 2018 the 17-year-old drill rapper Junior Simpson, aka MTrap, received a lifetime prison sentence for the murder of a teenager in south London. As part of the prosecution the court was told of lyrics in which Simpson had described the murder beforehand. "We're not in the business of killing anyone's fun," Detective Chief Superintendent Kevin Southworth of the Metropolitan Police told Business Insider in 2019, "we're not in the business of killing anyone's artistic expression — we are in the business of stopping people being killed." Referencing another incident where a drill rapper was convicted of torture, Southworth added: "When in this instance you see a particular genre of music being used specifically to goad, to incite, to provoke, to inflame, that can only lead to acts of very serious violence being committed, that's when it becomes a matter for the police."

However, in a 2020 article for the British Criminology Journal on the criminalizing of drill music, Jonathan Ilan, senior lecturer in the sociology department at London's City University, stresses the need for nuance in how lyrics are interpreted. "Contemporary UK drill is being treated as if what it speaks about is literal truth," he writes. He argues that many drill rappers exaggerate or fabricate violent stories because they know it attracts listeners: "This is not to deny that crime and violence take place involving drillers as either victims or perpetrators – rather, it emphasises not to view the violence as directly related to, caused by or evidenced by the music". Ilan also suggests that censuring drill does more harm than good, further alienating marginalised communities and ultimately exacerbating the conditions which lead to urban violence in the first place.

Drill fans and practitioners argue that in confronting the darkest truths of modern life and holding up a mirror to the most deprived, desperate and violent elements of society, their art resonates with young, disenfranchised listeners around the world – and that in itself is valuable. "This is music they can feel," says Corey Johnson. "They can feel that this is the voice of what's happening. So you're getting kids in other countries saying 'this is what's happening for me, this is what's happening on my streets'." He adds that, rather than aggravating urban living conditions, drill now offers a proven path to a better life. "Because of a lack of social and economic opportunities, the music's becoming a business. It's becoming more positive than negative."

Johnson says the harsh realities that gave rise to drill should be neither denied nor censored, comparing its reflection of gang violence to the prevalence of domestic violence narratives in early blues music. "Maybe the media never looked at it like that, but a lot of things are birthed from hardship and pain. Same way that behind more or less every fortune there's a crime." What's also clear is that, for many, drill is no longer even bound up in braggadocio or talk of killing opps. Given that gang conflict is a predominantly male phenomenon, perhaps the receding importance of violence in drill music is linked to the rise of women in the drill scene. While artists like Sasha Go Hard and Katie Got Bandz played a crucial, understated role in Chicago drill's early days, UK drill rappers like Shaybo and Ivorian Doll – who was recently crowned "Queen of drill" – are now reaching levels of stardom that rival the men.

The future of drill

No matter how it's policed, drill's global rise feels unstoppable. At time of writing Ghana's drill scene is fast becoming the hottest in the world, completing a loop which, before London, before Chicago, even before hip-hop parties in the Bronx, began with Jamaican sound systems and, before that, the African drum. "We as Africans, the drill speaks to us differently," says ChicoGod. His definition of drill is broad, progressive, dynamic. "Drill is a lifestyle. It's about what we see, go through in a society, what society has made us. We talk about the good, we talk about the bad." For him, liking drill suggests open-mindedness in a listener. "Cos the people listening to that sound, I'm sure, have decided to listen without trying to judge the person. Not everybody likes it. And if you like it, then you relate to it, in some way, somehow. Anybody can relate to it, you just have to listen. You just have to pay attention to what the person is saying."

Female drill rappers like Ivorian Doll are now reaching levels of stardom that rival the men (Credit: Fireshone)

Less progressive perspectives remain prevalent too, however. There are still drill fans who seem more interested in crime – and specifically murder – than music. On YouTube, Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok, fans have been known to post "scoreboards" awarding points to drill rappers for their alleged involvement in attacks on opps. As well as frequent tabloid attention, such practices have attracted criticism from people with close connections to the drill scene. Sayce Holmes-Lewis, founder of mentoring organisation Mentivity, was with drill rapper Rhyhiem Barton, aka GB, shortly before he was killed in 2018. Holmes-Lewis told Sky News he had seen people bragging about Barton's death on social media. "It was sickening, and it made me severely upset," he said, adding that such posts were likely to provoke more violence if they were not removed.

As drill looks to the future, divisions between drill musicians may deepen: some will cling to the sound's murderous origins; some will use violent lyrics that are merely metaphorical; and some will champion drill as a musical style that has long since transcended its violent roots. While it may always be divisive and densely complicated, drill is now firmly entrenched in modern pop culture, influencing mainstream pop stars, conquering audiences around the world and reaching millions of listeners. For ChicoGod, there's a simple reason for its popularity. "You realise that there's more to it than what people think, that it's just the violence and that. Yeah, for sure, it's the violence, but at the same time, it's not that deep. People just wanna dance."

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter .

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20210607-the-controversial-music-that-is-the-sound-of-global-youth

0 Response to "White People Listening Gangsta Rap Funny"

Post a Comment